The following appears in Organization Development Review, Winter/Spring 2020, Volume 52 Number 1. It is co-authored by myself and Heather Berthoud. A PDF of the formatted article as it appears in the review is available here.

______________

Every day we use our “self”. How did we learn to do this consciously? And, how can we teach others to be more aware of their “self” and be more intentional and effective in their Use of Self? For several decades we have both been exploring these questions in our own lives, through our work as coaches, consultants, facilitators, teachers, family members, friends, and community members.

Our goal is to share some of the experiences and lessons learned in our journey to help others gain awareness, develop capacities, apply, and continue to develop their Use of Self in the context of their professional work. Many of our insights are drawn from experiences teaching graduate courses in the Use of Self in professional practice as well as interpersonal and group dynamics. We will explore three key frameworks that we use to teach Use of Self and the process we use to manage awareness and capacities at multiple levels of systems—individual, interpersonal, group member, and group as a whole. We recognize that learning and development do not end when an educational program ends, and we offer our methods to encourage an appetite for ongoing development. We conclude with challenges and opportunities for the work ahead.

Miller (1976), referring to the distinctions William James made “knowing about” and “knowing of acquaintance”, notes that “knowing about” is about the acquisition of readily existing knowledge and involves intellectual or cognitive processes whereas, “knowing of acquaintance” is learning from experience starting with oneself. As a prerequisite for knowing more about the roles and relationships in which one is involved and about managing oneself in them, one must learn more about oneself. Philosophies and wisdom traditions through the ages and across continents have been built on describing the animating force that universally and particularly describes human beings.

Saint Augustine discovered interiority as a philosophical principle through his reading of books by Platonist disciples in which the quest to “know thy self” were so prominent. With “know thyself”, Aristotle recognized a distinction between action and the motivating forces of the actor. Whether through reason and/or will, people can direct their actions by developing consciousness of their intentions, motivations, and capacity. Similarly, Asian wisdom examines interiority through contemplative practices, which map self-development to discover the causes of human behavior and collective social conditions. Critically, all traditions are centered on the ability of the individual to be effective in the social circumstances of the age. That is, Use-of-Self is not a mere indulgence; it is an understanding of self, so that self can be deployed most effectively in contexts, whether interpersonal, group, or organizational.

“… Use of Self is knowing and deploying all aspects of our personhood (cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and spiritual) and applying that knowledge. Expanding Use of Self comes from self-awareness, reflection, continuous learning, and feedback, all of which serve to hone and expand our mastery” (Berthoud and Bennett, 2020). An expanded and fluid Self that sees, feels, knows, and can act appropriately in a given situation is what makes us effective in multiple contexts (Jamieson, Auron, and Shechtman, 2010). When talking about Self as an instrument, Tannenbaum and Hanna (1985) described Use of Self as social sensitivity and action flexibility. More than a mere technique, Use of Self is an approach to the practice of OD and leadership that emanates from, and is rooted in, the core of the person. This assertion suggests that the OD professionals and OD-oriented leaders and managers must be grounded in a mature and realistic sense of Self in order to appropriately judge a situation and their response to it. Use of Self manifests in several ways:

- how we look, talk, and present ourselves;

- the invisible parts of ourselves and our personalities, such as attitudes, values, motivations, biases, fears, assumptions, anxieties, feelings, habits, self-esteem, intuition, and hidden selves;

- the actions we take;

- the decisions we make;

- the choices we pursue; our styles and preferences; and

- the strengths, experiences, intelligences, knowledge, and skills we bring to each situation.

Use of Self is further influenced by many factors, including social identities (e.g., age, ethnicity, gender, national culture, sexuality, etc.), life and family histories, intentions, personal agency, self-efficacy, and levels of consciousness, self-awareness, and defensiveness (Jamieson, Auron, and Shechtman, 2010). Therefore, as Leary (2004) suggests, “the self is at once our greatest ally and our fiercest enemy, and many of the biggest struggles that people face in life are directly or indirectly the doing of the self” (p. 186). For OD practitioners, Use of Self means being aware of Self, attentive to the needs of others, mindful of context, and in service of mutual good. And, Use of Self for leaders is essential for deploying a full range of capacities and achieving desired results in a particular role.

Use of Self is particular and all encompassing. Mastery of it creates a paradox, because it calls for awareness and knowledge of a Self that is infinite in its possibilities, while finite in its realization. To realize individual potential, we must recognize the role the Self plays in fulfilling it. The expanding ability to see Self and to make choices is the ongoing work of the OD practitioner and leader. Therefore, “. . . by paying close attention to what is going on inside us and clearly perceiving the limitless world beyond our Self, we can substantially increase our own capacity to contribute to the common good while engaging in the process of individuation and self-differentiation—the unfolding of our unique Selves over the course of our lifetime” (Seashore, Mattare, Shawver, and Thompson, 2004, p. 56).

Evolving Frameworks for Teaching Use of Self

Kolb and Kolb (2005) assert that human development is substantially determined by learning and how individuals learn directs their personal development. Fenwick (2003) writes about the nature of experience and learning from and through experience. She notes different dimensions of experience, including those in which there is an immediate encounter in the here-and-now, whether planned or unplanned, those in which one learns by listening to and reading about the experiences of others and imagines themselves in that encounter. Other types of experiences are simulated, relived, experiences recalled, collaborative experience, and introspective experience. In our teaching, we rely on all of these modes of experience in addition to kinesthetic engagemen such as dance or other embodied action. Because Self is necessarily about interiority, each student’s response is unique, to the experience and whether it is even registered as experience, and then to the meaning that is derived from experience. Furthermore, Self exists in, affects, and responds to all levels of system—individual, interpersonal, group member, and group as a whole—so as teachers we must also be aware of all levels in order to support student awareness and development.

“…self exists in, affects, and responds to all levels of system—individual, interpersonal, group member, and group as a whole—so as teachers we must also be aware of all levels in order to support student awareness and development.”

At the same time, because teaching Use of Self is necessarily done experientially, and is about bringing into awareness what is out of awareness, participants can be surprised, sometimes uncomfortably, when confronted by their unknown and/or disowned aspects of self. Yet such work is essential to expand the affective and behavioral range and develop the agility needed for varied situations (Jamieson, Auron, and Shechtman, 2010; Rainey and Jones, 2014; Seashore, et al., 2004). Without such exploration and discovery, practitioners and leaders are limited to their myopic view of circumstances and possible responses. Furthermore, they are less likely to understand the potential range of perspectives and, therefore, responses available to them. Without knowing their own animating forces and fears as such, they may not even know that they are acting out of circumscribed understanding.

One challenge for the student, and for us as teachers, initially, was the seemingly random nature of experience and available lessons. Over time, we have evolved to rely on a few foundational models that guide both students and instructors through ever expanding application of Use of Self. Using those basic models, we can provide opportunities for students to experience and become aware of self at simple to complex levels of systems, i.e. individual to group while drawing on many frameworks, models, theories, and concepts that help illuminate the foundational models.

Many theories, models and frameworks related to human development, conflict, emotional intelligence, interpersonal and group dynamics explain the development and use of Self and are resources we draw on. As a way to organize learning of such a vast field, in our teaching, we use three specific models to frame the learning and development experience 1) Choice Awareness (Patwell and Seashore, 2006), 2) Change Mastery (Bennett and Bush, 2014), and 3) Reflective Practices (Brookfield, 1995; Johns, 2009; Schon, 1983, 1987). They form a base upon which all else can be built.

Choice Awareness Matrix

Patwell and Seashore (2006) define a framework for attribution of choices which they call the Choice Awareness Matrix. Individuals may attribute their choices for action, decision, inaction, and even emotion to themselves or others. These choices may be conscious or unconscious (aware or unware). Choice attributed to others that is unaware, is called socialization, such as following the norms of a group, organization, or social culture. Automatic choices are attributed to the oneself without intentionality. Automatic actions include habit, routine, rote behavior without conscious decision or consideration of alternatives. Choices one is aware of and attributes to others are blame or praise, a giving over of responsibility for the action and its outcome. Accountability occurs when a person makes a conscious choice and attributes that choice to themselves. Through facilitated, experiential learning, we seek to help students move choices into the mode of accountability by helping them notice their attribution and consider their options, choices and impacts on themselves, others, and the group.

Change Mastery Model

Regardless of the capacity a student wishes to develop, such as face conflict with competence, listen effectively, present self with confidence, the change mastery model offers a map they can locate themselves on (Bennett and Bush, 2014). In order to make any change, one must first be aware of the behavior or habit of mind. Once awareness is raised, then the crucial step of accepting the desirability of change can occur. Without acceptance, there is no move towards adopting new behaviors, trying on new ways of being, seeing, or thinking. It is critical here that the person has support for what is usually an awkward stage of novice behavior. Despite a tendency to want to get things correct right-away, most people take time to integrate the new behavior into a more conscious competence. With continued practice and feedback,— adopted behavior is effortless and the person can be creative in its application—that is, mastery occurs.

Reflective Practices

Drawing on the work of Aristotle in Nicomanchean Ethics, William James suggested “that there is a fundamental difference between knowing about, the product of reflection and abstract thought, and knowledge of acquittance, which drives from the direct experience of situations” (Stein, 2004, p. 21). Learning and experience are interconnected. And, later, Kolb and Kolb (2005), among others, noted that learning is a cyclical and iterative process beginning with concrete experiences, observations and reflection on those experiences, development of a theory about those observations and reflections, and active experimentation focused on the practical implications of learning.

We see reflective practices like journaling, meditation, and discussion as essential for learning. By reflecting on internal experience and external events, including one’s impact, students learn to notice what is happening as it is happening and to notice their relationship to those events. They begin to notice their own patterns of response, and in a group setting, can see that others have different patterned responses to similar events. Continued curiosity allows for reflection on how those patterns develop, whether conditioned by social context and identity e.g. immigrant status, age, sexual identity, race, etc. or biography. And, once patterns and the purposes they serve are discovered, students can make conscious choices about the actions and thoughts they make next.

Our Integrated Approach

Each of these foundational models and practices is used to build students’ effectiveness at multiple levels of each system. We intentionally build opportunities for students to examine each level of system in turn and recursively. We know that higher levels of systems are harder for people to discern, especially when they are participants in them. By creating tight focus on a level of system for any given experience, we help direct students’ reflection. For example, a given experience, e.g. a conversation, structured activity, serendipitous occurrence, can be reviewed using questions that focus on distinct levels of system such as:

- Self

- What do I notice about my physical sensations as I witnessed…?

- Under what circumstances am I likely to make similar choices? What other choices might exist? What would it take for me to make them?

- Interpersonal

- How do I interact with a person with a different style preference?

- When am I attracted to/pulled back from someone else?

- What is the dynamic between these two people? How does it come about?

- Group member

- When I did X, what impact did it have on the group?

- What role do I play in the group? How is it useful? Not useful?

- Group as a whole

- What matters to the group as a whole?

- How do you characterize the temperament of the group?

- What behaviors would support improved group decision-making?

Critically, these reflections on the experience in the classroom, are examined as typical dynamics of organizational life. The thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that students experience in the classroom are not unique to that setting. Rather, they typify how these students in particular, and people in general, can present themselves in work and other settings. The interpersonal dynamics, group member roles and group culture are reflections of and proxies for groups and organizations participants contribute to and witness outside the course.

Encouraging Ongoing Learning

Though we teach Use of Self, we are clear that course completion does not signify mastery. In fact, it may only signify awareness or acceptance in some cases. We begin by establishing the courses and class sessions as moments in a lifetime. The purpose of the moment is to set a direction, make the existence of a path known, to advance along the path, and whet the appetite for the journey of continued learning and development. Through descriptions of our own learning journeys and those of our mentors, we establish examples of life-long learning. Through recognizing even small changes in behavior, as in a well-timed or directly worded statement, a joining instead of ignoring a comment or person, we encourage the celebration of small victories and the possibility of expanded and sustained success. The reflection of what will be done in the future, in the next encounter within the course and the next weeks, months, years, after the course, students are invited into a process that unfolds over decades, not just in the confines of a program.

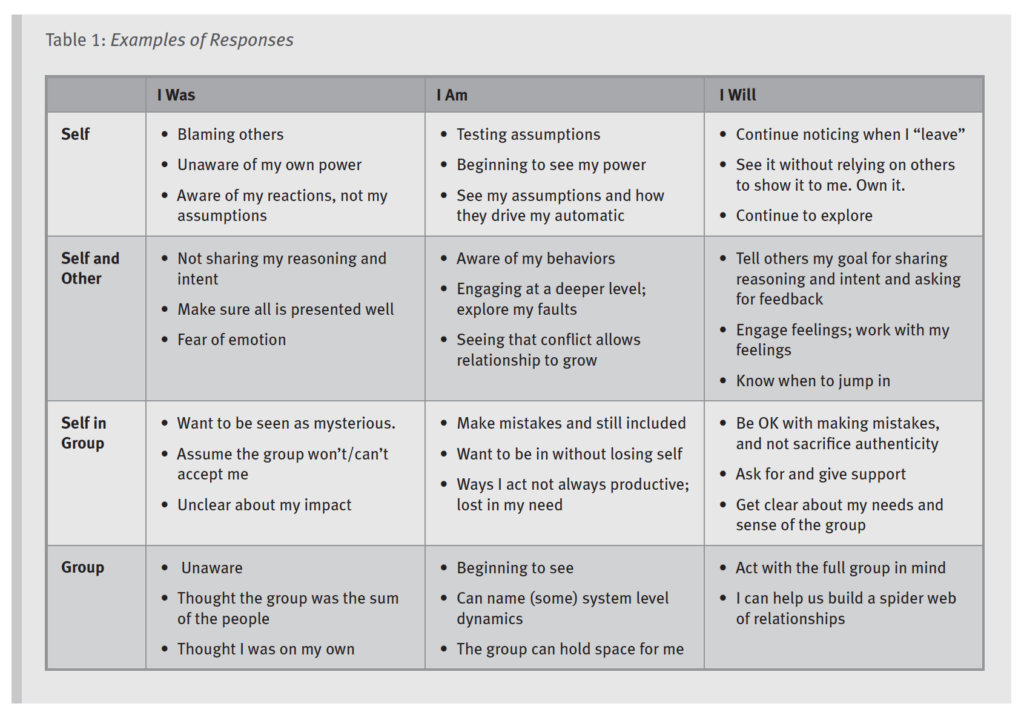

We typically close courses and workshops on Use of Self with a reflection of where the students understand themselves 1) to have been when they entered the course, 2) where they are now, and 3) what they will do in the future. The construct of the reflection is intended to reinforce the idea of a journey already begun, and that can evolve. We also reinforce all levels of system by asking for reflection at all levels. In Table 1, we provide examples of responses we have heard.

Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

As more attention is focused on developing Use of Self, the opportunities to learn and develop a body of knowledge abound. We have simply shared our experiences and learning. We encourage others to continue the work to document, research, and share ways to teach and learn about the use of one’s self. This work has decades, if not centuries, of historical experience, using various tools and ways of teaching aspects of the work, and a growing body of knowledge about the theory of Use of Self. Relatively little has been written to share best practices and learning about how to teach it. While there may never be—or should be—a single theoretical or practical framework for Use of Self, it would be useful to see the work of scholars evolve into a set of theories of teaching approaches that can be studied, taught and practiced. Those engaging the development of Use of Self need an andragogy. This will allow those who are engaged in teaching—formally and informally—to identify, share and evolve a body of knowledge that extends beyond the “what” of Use of Self to the “how to teach” Use of Self. This will support best practices and evaluation of those practices for efficacy.

We need animators, as Boud and Miller (1996) refer to those who help people learn without formal teaching. Brookfield (1995) argues that learners’ experiences constitute a rich resource for problem-solving and suggests that a critical task for animators is to develop learners’ confidence in the usefulness of these experiences. This is contradictory to common expectations of learners, which is usually that the expert will teach them. Just as coaches and mentors can be developed, so can animators. And, finally, we must develop ways assess learning and development of those who participate in educational experiences related to Use of Self.

Conclusion

Developing Use of Self as OD practitioners and leaders is an extensive undertaking, because it involves understanding and effectively using all aspects of ourselves to serve change in others, whether as individuals or larger systems. As practitioners and leaders, it is important not to focus on merely wielding techniques but to present the fullness of one’s being in support of the continued development and use of Self. It is through that fullness of being that one has resonance with clients and colleagues to engender the confidence and trust needed to receive the techniques, and to learn, and recover should things not go according to plan. The more we can see the essence of our Self and understand our Self, the more we can support others in seeing their Selves. The greater our mastery of Use of Self, the greater the potential impact on the systems we are in. Regardless of how we view Self, there are multiple and overlapping ways to develop it towards mastery, provided we are intentional and diligent. Only then are we able to have the desired impact with individuals, groups, organizations, and even larger systems, if we choose.

References

Bennett, J. L., & Bush, M. W. (2014). Coaching for change. New York, NY: Routledge.

Berthoud, H., & Bennett, J. L. (2020). Use of self: What it is? Why it matters? & Why you need more of it? In S. H. Cady, C. K. Gorelick, & C. T. Stiegler (Eds.), The collaborative change library: Global guide to transforming organization, revitalizing communities, and developing human potential. Perrysburg, OH: NEXUS4change.

Brookfield, S. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Boud, D., & Miller, N. (1996). Synthesising traditions and identifying themes in learning from experience. In D. Boud & N. Miller (Eds.), Working with experience: Animating learning (pp. 14–24). London: Routledge.

Fenwick, T. J. (2003). Learning through experience: Troubling orthodoxies and intersecting questions. Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing.

Jamieson, D. W., Auron, M., & Shechtman, D. (2010). Managing use of self for masterful professional practice. OD Practitioner, 22(3), 4–11.

Johns, C. (2009). Becoming a reflective practitioner (Third ed.). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2005). Learning styles and learning spaces: Enhancing experiential learning in higher education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(2), 193–212.

Leary, M. R. (2004). The curse of the self: Self-awareness, egotism, and the quality of human life. Oxford: Oxford Press.

Miller, E. J. (1976). Task and organisation. London: John Wiley.

Patwell, B., & Seashore, E. W. (2006). Triple impact coaching: Use-of-self in the coaching process. Columbia, MD: Bingham House Books.

Rainey, M. A., & Jones, B. B. (2014). Use of self as an OD practitioner. In B. M. Jones & M. Brazzel (Eds.), The NTL handbook of organization development and change: Principles, practices, and perspectives (Second ed., pp. 105–126). San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

Schon, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schon, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Seashore, C. N., Mattare, M., Shawver, M. N., & Thompson, G. (2004). Doing good by knowing who you are: The instrumental self as an agent of change. OD Practitioner, 36(3).

Stein, M. (2004). Theories of experiential learning and the unconscious. In L. J. Gould, L. F. Stapley, & M. Stein (Eds.), Experiential learning in organizations: Applications of the Tavistock Group Relations Approach (pp. 19–36). London: Routledge.

Tannenbaum, R. T., & Hanna, R. W. (1985). Holding on, letting go, and moving on: Understanding a neglected perspective on change. In R. T. Tannenbaum, N. Margulies, and F. Massarik (Eds.) Human systems development. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

______________

Post © 2020, John L. Bennett. All Rights Reserved.